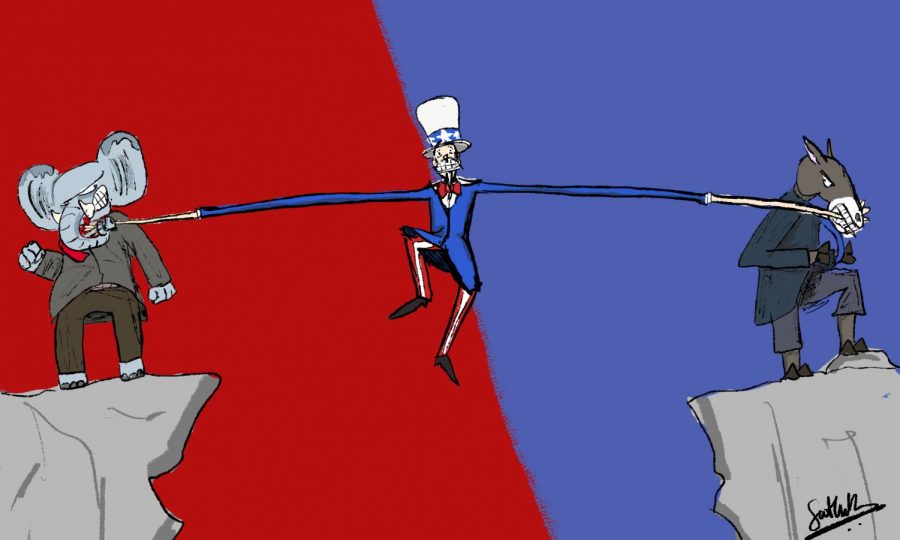

The recent presidential election, U. S. Capitol riot, and the second impeachment has brought up the idea of political polarization. Politics play a big role in society and are thus often encountered in many places, including schools. Since schools are emphasized to be places of learning and acceptance, it can be difficult to consider polarizing politics in a fair way.

History teacher Maria Jarzabek often faces this problem. Jarzabek teaches a variety of social studies related courses including Sophomore Humanities, Current Issues, and U. S. History. Her courses frequently relate back to politics, resulting in her trying to find a way to keep her classroom as unbiased and accepting to other opinions as possible.

“There are no official guidelines, but there are unofficial guidelines,” Jarzabek said. “When we’re in school and we become social studies teachers, one of the big things that [the school] always tells us is to make sure that we don’t push our own political agendas on our students. If I’m doing my job as a good social studies teacher, you should not be able to tell which political party I affiliate with.”

When it comes to discussing politics, Jarzabek emphasizes the fact that it is not her job to tell students what to believe, but rather to teach them the facts so they can form their own opinions based on correct information.

“As a teacher,” Jarzabek said, “I should be presenting both sides of the issue and then letting you as a student decide which position you agree with.”

Current Issues, one of Jarzabek’s elective courses, discusses the current political climate significantly more than her other classes. Because of this, she must ensure that she is being as unbiased as possible and does as much research as she can on the topic before class.

“I’ll go to both conservative and liberal sites to get my information and see what are the commonalities in both to get the truth of what’s going on out there,” Jarzabek said.

In order to keep biased misinformation out of her classroom and discussions, Jarzabek teaches her students about bias and fake news right off the bat. This helps them identify the differences between the two rather than mistake one for the other.

“Really conservative students will come in and tell me that all liberal news sites are fake and really liberal students will tell me that conservative news sites are fake,” Jarzabek said. “I’ll have to tell them that that isn’t necessarily true, they just might not like what they have to say.”

However, it seems to Jarzabek that the future of discussions in her classes is uncertain. She has noticed that, even more so than last year, the polarization has been much more prevalent. Jarzabek does not teach a Current Issues course this current semester, but she is concerned as to what next semester’s class will be like.

“One of my fears is that I’ll have to tell a student that what they’re telling the class is a complete lie, and I’ve never had to do that before,” Jarzabek said. “Usually I can tell them that it’s an ‘interesting opinion’ or that it’s ‘out there,’ but this year I feel like I might have to tell a student ‘that’s false.’”

Jarzabek is not alone in this belief. Many other social studies teachers, such as Susan Wakelin, agree with a lot of Jarzabek’s points. They even add on to the “unspoken” guidelines that teachers in their department should follow.

“Sometimes [politics] will come up in department meetings at the beginning of the year,” Wakelin said. “Our curriculum coordinator will sometimes say something along the lines of ‘Just be careful with what you’re saying in the classroom and know your “clientele.”

Like Jarzabek, Wakelin also teaches several different types of social studies classes, including World History, Freshman Humanities, and AP U. S. History (APUSH). This means that she teaches a wide variety of students and thus faces a wide variety of opinions.

“The way that I run things is I act more like a mediator,” Wakelin said. “I allow for students to have their opinions and to bring them out, but I’m always asking ‘Where did you get your information?’ You have to come with facts that we can verify because if you’re talking about something that you saw on a Snapchat feed or something like that, then I’m sorry but I don’t really hold that as truth.”

Despite the fact that classroom discussions on controversial topics are prone to becoming heated, Wakelin recognizes that they are still sometimes necessary in order for her students to learn about current events.

“I want my classroom to be a safe environment for students with different opinions because we need to have these discussions and we’re going to have them as you can’t talk about things like Native American removal or slavery without bringing up American policy and government, which of course people are going to disagree on,” Wakelin said. “But at the end of the day, if we walk away and you say ‘I don’t agree with you’, that’s okay, but we’re going to be cordial and friendly to each other in [my class] regardless. This is what I always tell them: ‘If I hear that the conversation that we had in here went outside these walls and it got nasty, you’re gonna be in trouble.’”

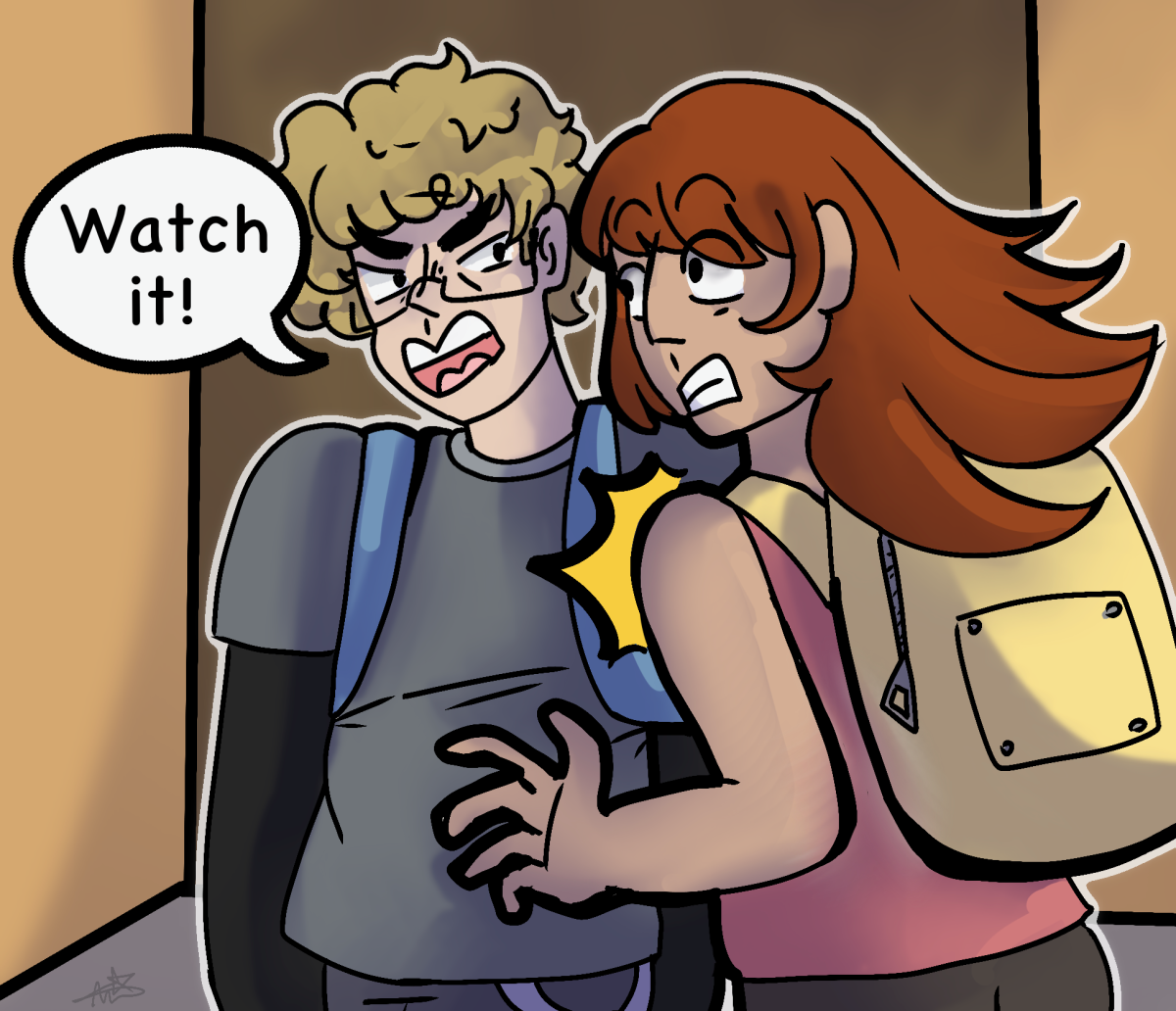

Like Wakelin said, it is true that political discussions often escape the classroom and become problems between students. Mediums such as social media and the internet have allowed information regarding politics to disseminate easier, especially within younger populations, which includes the student populace. While many try to remain nonpartisan, others are more openly opinionated, this leads to many disputes within the student body.

However, Londonderry High School also tries to embrace healthy political interactions through courses and clubs such as Model United Nations and Debate Team. As both a high school junior and an avid member of the Debate Team, Matt Villineau often faces this social dilemma.

“I know that a lot of students get upset at other people’s opinions pretty easily,” Villineau said. “I’ve seen friendships end over politics, and not that infrequently.”

As part of the Debate Team, Villineau is often faced with controversial subjects and opinions. However, according to him, it doesn’t become as polarizing there as one might think.

“We’re able to keep debate nonpartisan a lot of the time because we represent sides that we don’t agree with pretty constantly,” Villineau said. “It becomes difficult to tell what people actually believe.”

But when so many other people talk about politics outside of clubs, when is it safest to do so yourself? Villineau says that it is best to discuss polarizing topics amongst people you already have established relationships with.

“I only really talk politics with friends that I trust,” Villineau said. “In Debate [Club], we all know each other and are friends, so it’s so much easier than with students you don’t know well.”

While teachers can effectively remove misinformation from their classrooms and accept the opinions of everyone, it seems that applying that to the student population is far too difficult a task. Students will always be entitled to their own opinions, but it often comes down to friendships ending and people disliking each other over a disagreement on a political matter.

“In today’s climate it really seems like if you have a difference of opinion, then that’s not okay,” Wakelin said. “It’s not okay to just disagree anymore, but instead now it’s like: ‘I don’t want to ever talk to you and I don’t want to be friends with you.’ From a teacher’s perspective, unfortunately, that just seems to be how it is.”