It takes tedium to create genius.

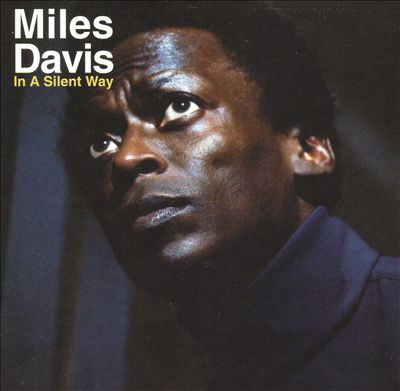

By 1969, Miles Davis’ sound had evolved past the traditional bebop trappings he had first risen to fame with, leading to a sort of creative rut that plagued his latest handful of studio releases. In short, he felt suffocated by the confines of the genre, and sought to branch out. It is this period of dissatisfaction, this bout of writer’s block, that first motivated him to break new ground in jazz.

In a Silent Way was Miles’ first foray into fusion. Studio B in CBS’ expansive New York City lot would be the birthplace of “Electric Miles.” The sessions, recorded over one turbulent day in February of 1969, were some of his most experimental, outlandish recordings to date. Miles’s Second Great Quintet of Wayne Shorter’s feverish sax, Chick Corea’s manic piano spasms, and the dual rhythm attack of Dave Holland on bass and Tony Williams on drums accompanied his deft trumpet work. What was new and unexpected was the inclusion of guitarist John McLaughlin and electric organist Joe Zawinul, whose unconventional playing styles and amplified instrumentation supplemented the classical quintet in a way few groups had dared to do before.

The early roots of Bitches Brew can be found on In a Silent Way, a mere year’s time before the former would be released. The lineup had solidified, the arrangements sufficiently tightened, leaving the ensuing sessions with a sheen of modernity that Miles had been sorely lacking of late. Fusion had been created.

What makes the record all the more impressive is the studio wizardry behind it. The songs were not recorded all in one take, as was traditionally done in jazz of the period; rather, Davis and McLaughlin culled through 210 minutes of audio, cutting and stitching it together like some sort of Frankenstein’s monster of a jazz album. Studio work such as this may have been commonplace in other genres at the time – Brian Wilson was slowly unraveling across the country in Los Angeles trying to splice together hundreds of hours of tape into the Beach Boys’s great unfinished white whale, SMiLE – but for Miles to do what he did was unparalleled in jazz. Overdubbing, unconventional microphone placement, even the mixing and mastering were unlike anything else in the era.

In a Silent Way stands out as a time capsule from the moment when Miles Davis first broke through the traditional and veered into legend. The two twenty-minute cuts that make up this record represent a change in the guard, both in Miles’ career and in jazz music as a whole. It is a landmark recording, and one that effortlessly captures a portrait of its creator, warts and all. It may not be as remembered as Kind of Blue, or as heralded as Bitches Brew, but what makes it a classic album is the groundbreaking amount of passion and drive that went into making it.

Serge Beaulieu

Nov 19, 2015 at 11:58 am

I remember being a high school student when I first heard Miles Davis’s electronic music. It was crazy stuff! Very educational article. Great job!